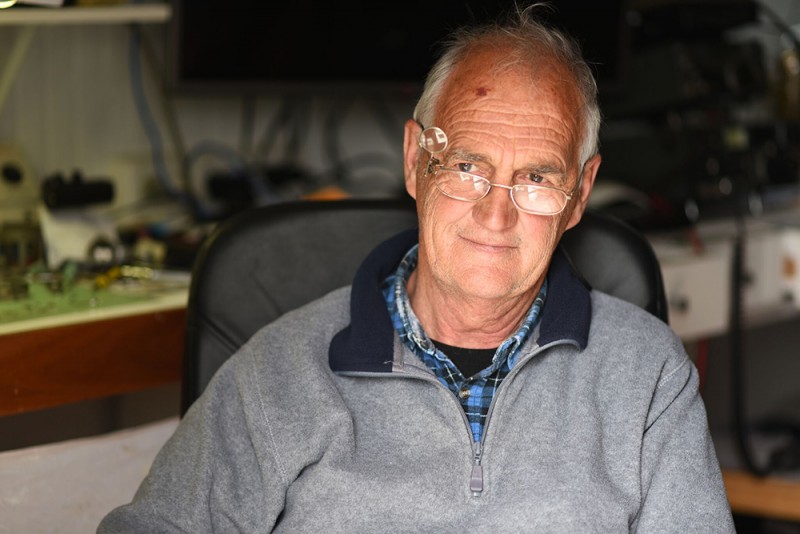

Jim Crowther, watchmaker, beekeeper, maker and fixer of objects large and small, picks up a screw with a pair of fine tweezers and holds it in my direction. “That’s not the smallest of them,” he says. It’s tiny. A speck so minuscule that, even looking closely at it, even knowing it for what it is, there’s no resolution beyond that of mere speck. “To the outsider, I suppose, it all looks small, but to us… it’s part of life.”

We are sitting in the workshop at his farm, and the house, which he built himself, commands three hundred and sixty degree views of the surrounding country – mountains, valleys, distant eucalypts. There’s a kelpie running here and there, attentively eyeing Jim. Stacks of honey jars catch sun in the windows.

There seems to be a metaphorical ft between watch repair and his bee-keeping – the many individuals that make up a hive, all working together. I mention this to Jim, and he waxes lyrical about these vital, tiny beings: “you start learning about what these little creatures do and it’s fascinating. They’ve all got their place.” He started out researching them for lucerne pollination, growing feed for cattle, but in the end the bees were more interesting than the hay.

Jim has run a number of jewellery shops in the mountains and out west, and opened first premises in Blackheath back in nineteen seventy nine: “I’m only a newcomer,” he says, with a wry smile, “I’ve only been there thirty years.” He closed his most recent premises in the village a year or so back: ‘Too many customers—“ he says, “I couldn’t get any work done.” When not working for the local bushfire brigade, of which he is the captain, or tending his bees, he divides his days between jewellery shops through the mountains, Lithgow, and beyond.

I think this is the first time I have heard of a business premises closing because of excess customers, and it seems to say a lot about the job that Jim has been doing since first commencing his apprenticeship, at the age of sixteen. There’s no shortage of work – more than he has time for – but there are so few apprentices entering the field, it is hard too keep up with the demands that jewellery shops place on him. Government cuts to TAFE funding, which tend to squeeze out the specialist, low enrolment courses like watchmaking, certainly don’t encourage new apprentices to come through. But I suspect that equally important is the idea of fixing things in itself, and our distance from it.

The erosion of the centrality of repair to our mindsets has been a gradual one, but it has accelerated markedly over the last few decades. It’s worth reminding ourselves that this is not, as it stands, implicit in the system, that it is not unavoidable. Our engagement with technology, although bound up with notions of advancement, and entwined with our contemporary conception of progress, is not out of necessity one of disposability. That is more about selling things, with obsolescence built into everything from fridges to iPhones, and software upgrades becoming interlaced with hardware upgrades. It’s this logic of disposability that needs to be brought into question, and which work like Jim’s pushes back against.

It is curious that, in a culture that celebrates the disposable, the update, to the extent that ours does, the supply of those who are capable of repair cannot keep up with demand. Jim has put a few apprentices through – “given back,” as he calls it. But although the nature of the gadgets we use is changing, we are certainly not using less of them: there would seem, then, to be a big future in device repair, if we can shift our thinking a little.

After we talk, he takes me through the house, to look at the wall clocks he has made. They’re beautiful objects, with intricate, shining mechanisms, rich in fine-grained timber that has been brought to a buffed shine with Jim’s skill at French polish. “If you make a clock, that’s something that will never ever be left behind,’ he says. “You are not the owner of a clock, you are the caretaker. And that will go on for generations.”

Berndt Sellheim