Professor Heidi Norman (Hamish Dunlop)

By Hamish Dunlop

It’s late in the day and I’m getting on the train at Blackheath Station. The sky is all the shades of orange and the air is still and quiet. When I walk into the carriage there is a group of teenagers talking loudly and laughing. I’m happy to see this and happier because they are wearing the rainbow colours. It’s a long way from Sydney where the Mardi Gras Parade is in full swing, but pride is no longer just celebrated on a 2.4km stretch in the city. This year, Anthony Albanese is the first Prime Minister to walk the walk. In his words, “This is a celebration of modern Australia. We’re a diverse and inclusive Australia.”

The Blackheath History Forum (Hamish Dunlop)

The event I’ve been at in Blackheath was held at the Gardeners Inn. It was the first meeting of the Blackheath History Forum in 2023 and Professor Heidi Norman was invited to speak about the Voice to Parliament. She is a Gomeroi woman from northwestern New South Wales. She starts her talk by paying her respects to the traditional owners of this land, the Dharug and Gandangara peoples. Her gaze turns to the railway line you can see looking out the pub windows. She talks about how her Aboriginal family worked in the Pilliga Forest where Cyprus Pine was harvested for railway sleepers. They contributed one way or the other to radical changes in the forest.

In the present day, the Gomeroi native title claim extends to the Pilliga Forest. It’s also the site of the Santos Narrabri Gas Project. Professor Norman says that governments have backed the venture at both state and federal level with cross party support. This is a point of pain and opposition for the Gomeroi people. They have filed an appeal against the National Native Title Tribunal’s decision to permit the contentious project. The Tribunal ruled that the public benefit of the project outweighed the objections and any environmental concerns. Santos has argued that the project will provide energy security and act as a transitional energy source. For Professor Norman, this highlights an inability of political mobilisation or action through the courts to defend and assert Indigenous rights.

Professor Norman is an advocate for the Voice to Parliament, the referendum that has come out of the Uluru Statement from the Heart. The Uluru Statement was released in May 2017, asking for Voice, Treaty and Truth. It was generated through the First Nations National Constitutional Convention. The Uluru Dialogue is a group of First Nations and non-Indigenous community leaders, law scholars and advocates based at the UNSW Indigenous Law Centre. They characterise the Statement as asking “Australians to walk together to build a better future by establishing a First Nations Voice to Parliament enshrined in the Constitution, and the establishment of a Makarrata Commission for the purpose of treaty making and truth-telling.”

There are many voices in this debate. There is a political split, drawn primarily down partisan lines. There are also differing positions among Aboriginal leaders and communities on the best way forward. It would be impossible in such a debate for hostility and racism not to play a part. “It reminds me of the Same Sex Marriage plebiscite and the terrible hostility around that,” Professor Norman says. “It is possible when we look back at the successful Yes vote that we forget how fraught the process was.”

The then Liberal–National Coalition government pledged to facilitate a private member’s bill to legalise same-sex marriage. MPs from both the Coalition and the opposition Labor Party allowed their MPs a conscience vote, recognising the sensitivity of the issue. The voluntary postal survey was held between September and November in 2017. Despite cross-party support, two legal challenges were raised. One questioned the authority of the Australian Bureau of Statistics to conduct the survey and the other opposed the government’s right to fund the survey. The High Court of Australia found that both were lawful; both legal challenges failed. In the end, 79.5% of eligible voters voted and 61.6% of those voted yes. As a result, the rainbow colours and acceptance of difference are more present in our society. But they were hard fought for, and pain and discomfort surrounded the vote.

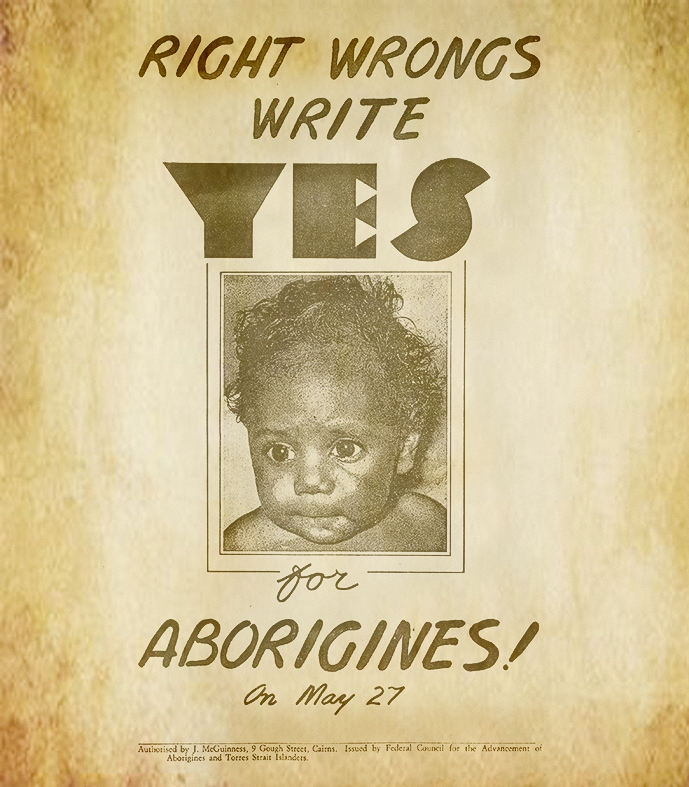

The 1967 Referendum (State Library of South Australia)

The 1967 Referendum was no different. In the broader public, then and now, we marvel at the more than 90% of people who stepped out and voted Yes. It is a point of pride that as a nation, we overwhelmingly agreed there should be fairness and justice for all. The reverberations are still palpable. It plays a significant part in the context that led to the Uluru Statement from the Heart. Professor Norman says that we should remember that the 1967 Referendum was a carefully calculated and risky political tactic. There was division between advocates, allies, politicians and Aboriginal groups and individuals. One camp focused on achieving constitutional change so that the Commonwealth had power to legislate in relation to Indigenous peoples. The other wanted recognition of Aboriginal land rights. The decision to proceed with the Referendum was hotly debated.

Professor Norman says that while the 1967 Referendum appealed to nationalism, it involved modest changes to the Australian Constitution. These changes gave the Commonwealth concurrent powers with the states to make laws and policies with respect to Aboriginal people. This made it possible for the federal government to play a role in addressing Aboriginal disadvantage. Subsequently, governments adopted various positions with respect to Aboriginal affairs. This included the creation and dissolution of different representative bodies. Professor Norman views each of these bodies as an Aboriginal voice.

The Whitlam government adopted the policy of self-determinism. It established the first Department of Aboriginal Affairs and the first representative body: the National Aboriginal Consultative Committee (NACC). Malcom Fraser’s government reviewed the NACC and replaced it with the National Aboriginal Committee. The members of each were democratically elected. The Hawke government created the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Island Commission (ATSIC) which lasted from 1990 until 2005. The Howard Government introduced the language and policy of ‘Practical Reconciliation’. The policy aimed to address temporary disadvantage among otherwise equal citizens. However, during its tenure, his government also disbanded ATSIC. Professor Norman says the Aboriginal voice was lost, one that was representative, democratically elected and funded.

Since the 1970s, Australian Governments have tried with varying success to give Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples a voice in policy decisions that impact their lives. History shows that attempting to provide mechanisms to hear and act on Aboriginal voices is not new. But the success of these voices in informing policy has suffered from the whims of the government of the day. That is why having a Voice protected by the Constitution is key.

Professor Norman at the Blackheath History Forum (Hamish Dunlop)

Professor Norman’s talk comes to an end. It’s been about learning from history when thinking about the proposed Voice to Parliament. We rightly mythologise the big political moments in our nation’s history in the formation of our national identity. However, beneath these moments lie conflicting views, compromise, pain and detailed political strategies. The Voice to Parliament is no different. But I think it is worth zooming out, looking at the history of change in Australia and imagining what this moment in history could look like when we look back from the future.

At the event lounge at the Gardeners Inn, the floor opens for comments and questions. There are a wide range of views voiced. Professor Norman fields questions for about half an hour, the same length as her entire talk. She is considered and thoughtful in her answers and actively avoids polarising statements. Out of this and the dialogues with the questioners, a space is created for thinking and reflection.

After the talk, people funnel into the bar for dinner and drinks. What I notice is that despite my own initial view on the matter, I am more open to finding out about what everyone thinks and is saying about the Referendum. Later, on the train, I think about the ideas and issues discussed today. They will no doubt be explored further in our wider community because of the Blackheath History Forum event. I’m also conscious that the event has taken place in one of our modern town squares. A chat over a beer in the pub with someone is something that shouldn’t be underestimated.

To find out more about the Blackheath History Forum visit: https://blackheathhistoryforum.org.au/

Understanding the Voice

Community Town Hall – Sunday 30 April – 3pm

Organised in collaboration with Blue Mountains City Council Mayor Mark Greenhill, this is an interactive event and a great opportunity to learn more about the upcoming referendum to recognise Aboriginal and Torres Strait Island though a constitutionally-enshrined voice.

The panel discussion will include special guest, renowned Indigenous film director, writer and producer, Rachel Perkins.

The community town hall meeting will be held on Sunday, April 30th, at 3:00 pm at the Blue Mountains Theatre & Community Hub, 106 Macquarie Road, Springwood. It will also be streamed online for anyone unable to make it in person.

This town hall is a free ticketed event. RSVPs are essential for both in person attendance and online streaming. Register here

Voice Town Hall Meeting

3:00pm-4:00pm

Sunday, April 30th

Blue Mountains Theatre and Community Hub

106 Macquarie Rd Springwood

An Auslan interpreter is being provided for both online and in-person attendees.

This story has been produced as part of a Bioregional Collaboration for Planetary Health and is supported by the Disaster Risk Reduction Fund (DRRF). The DRRF is jointly funded by the Australian and New South Wales governments.