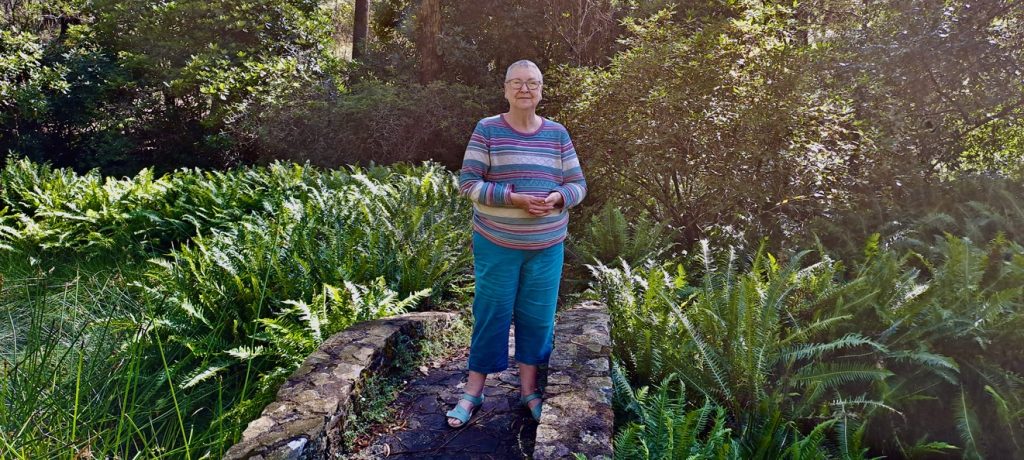

Deborah Wells in the Blackheath Campbell Rhododendron Gardens (Hamish Dunlop)

By Hamish Dunlop

Hamish Dunlop interviews Deborah Wells in the Blackheath Campbell Rhododendron Gardens. She shares how a group of passionate and dedicated volunteers have created a community space that is a haven for all species, and how they’ve helped it recover from drought, fire, flood and pandemic.

I’ve just turned down Bacchante Street and I’m following a little silver Soul down the sloping hill toward the Campbell Rhododendron Gardens in Blackheath. I’m betting with myself that the driver is going to be the person I’ve come to interview today. The silver Kia parks neatly into the far-left space, and I pull in next door. We both exit our cars at the same time. The woman says “Hamish!?” and I say “Deb?!” She beams at me with a bright smile. This lovely start to our meeting sets the tone as we wander about the Blackheath Campbell Rhododendron Gardens.

Deb starts by telling me about the last few years. It’s a familiar story – drought, fire, flood and pandemic. At the heart of this story is a combination of resilient land and remarkable people, and how they’ve overcome these adversities. It’s about volunteers who each have their own special relationship with the Gardens, and who are part of an amazing history. These gardens were built by locals who were motivated to create a beautiful place for the community to come and enjoy. They did everything from the earthworks, the roads, the paths, the plantings, the lake and the buildings.

Native and introduced species living in harmony

It was Dick Harris and Robert Ibe Sorensen’s vision. ‘lb’ was the son of the famous Paul Sorensen, a Danish-born Australian landscape gardener and nurseryman who designed and planted over 100 gardens in the upper Blue Mountains. One of the unique features of the Gardens is that native and introduced species live in harmony – a canopy of Eucalypts with an understorey of rhododendrons and azaleas. Ib and Dick wanted to find out if Eucalypts that flourish in alkaline soil could successfully grow alongside acid-loving rhododendrons. The spectacular results of that experiment can be seen today.

Native and introduced species growing side by side (Campbell Rhododendron Gardens)

How do the Gardens survive financially?

2019 was the 50th anniversary of the Gardens. It was a celebration in lockdown. Deb tells me that a strong group of women kept things going during Covid by working within their five kilometres from home. “Digging a hole was exercise, as was planting a tree, as was carrying the water and putting the water on the plant – the work got done, sensibly and safely.”

An important percentage of the money that keeps the Gardens going comes from the $5 charge taken at the booth outside the Lodge. It also comes from the Welcome Weeks that start on the long weekend in October and go through to the Rhododendron Festival Weekend, which is the first one in November.

“We turn the Lodge into a tearoom. We brew beautiful Fish River coffee and Lim from the Blackheath Bakery Patisserie makes us scones – just for us for our Welcome Weekends. We put in our order each day and go and pick them up. We call them Aussie cream teas, not Devonshire teas because we use fresh not clotted cream.” The volunteers contribute a wide range of delicious home-baked treats and sales during this month provide the basis of the Gardens’ working capital for the next 12 months.

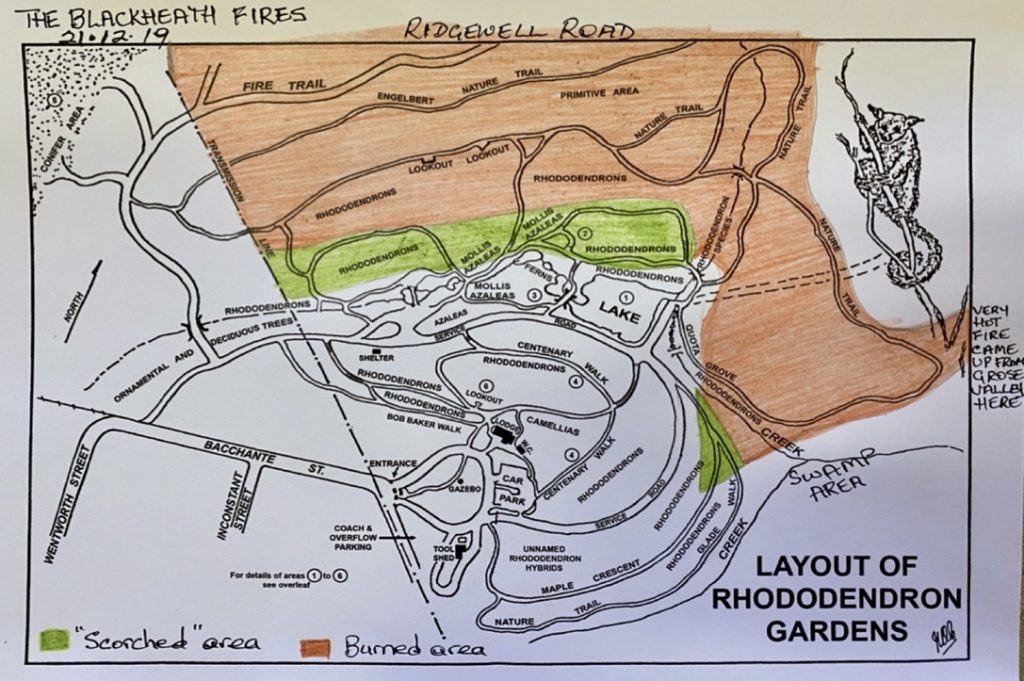

The devastation of the December 2019 Fires

I ask about grants, given Welcome Weekends have not been possible for the last few years. Deb says they occasionally get grants to deal with major projects such as swamp management, rebuilding fences and the cost of the arborist to take out more than 100 trees that were burnt beyond saving in 2019. They received two grants specific to post fire recovery.

Fire Tree (Julia Hanley)

The trees that weren’t in danger of falling were left as habitat for hollow-loving animals. The ones that were cut were rolled into the gullies to help stop erosion. Wood that couldn’t be chipped was given to people for firewood. Deb says they do as much as possible to consider the overall ecology of the Gardens. “This place is for everyone and everything” she says. “It’s about care and conservation.”

A fire-blackened Gardens (Blackheath Campbell Rhododendron Gardens)

She was at the Lodge when the smoke could first be seen to beyond Ridgewell Road. The Grose Valley fire tore up the northwest side of the 18-hectare Gardens, destroying a third of it.

Map of burned areas in the Rhododendron Gardens (Courtesy Campbell Rhododendron Gardens)

I have only been here once before when my Dad came to visit in late 2022. I brought him here because he grows rhododendrons. We were awed by the serenity of the valley and the towering specimens that were late to flower that year because of the rain brought by La Niña. I remember some blackened rhododendron stumps. Remarkably, some of them had luminous green growth squeezing out of charcoaled trunks.

A rhododendron grows in a fire blackened area (Hamish Dunlop)

Since the fire, the Rhododendron Society has replanted more than 400 rhododendrons. The original rhododendrons came from Nepal. Dick Harris had a licence to import them – both he and Ib were nurserymen. Deb tells me that in the fire, the Species Valley that contained all the original plants, was completely destroyed. Mount Tomah Botanical Gardens has generously offered to replace some of the species. The Eucalypts in that part of the Gardens were also badly burned. From where I’m sitting in the Lodge, I look across the valley towards that part of the Gardens. The sun is shining and there is a sea of new blue-green leaves dappling the rhododendrons and the blackened trunks below.

“Nature is more resilient than we think sometimes.”

Deborah Wells

Providing habitat for wildlife after the fires

Peter Ridgeway ( Campbell Rhododendron Gardens)

“What volunteers and others did after the fires was extraordinary too. Peter Ridgeway from National Parks sent us diagrams for the creation of nesting boxes for various different critters and the Blackheath Men’s Shed made them up. The ones for micro bats had to be up in the car park where the bats can just zoom straight in with nothing in their way. Peter later gave a talk to us on making boxes for your own garden.”

Nesting boxes high on the tree trunks (Hamish Dunlop)

“These little ones over here are above feeding areas, the banksias and grevilleas. The big ones you can see down the bottom, on the Eucalyptus Oreades, are for brushtail possums. We just have some wonderful people who contribute to the Garden. After the fires Mikla Lewis from Blue Mountains Wild Plant Rescue came and did a walk through with us. She said just leave it for a year, see what happens. And we did, and the natives came back beautifully. Everything came back beautifully.”

Deborah Wells

Wildlife Camera (photographer unknown)

More people came after the fires. Emma Spencer, who was doing a wildlife study, put wildlife cameras up. In the first little while it was quolls and swamp wallabies and eastern greys and owlets. They were happy with the lack of feral animals. “There was one fox and no feral cats”

Oliver Kelly, a PhD Candidate from Newcastle University who was studying the recovery of frogs in the Blue Mountains came because of the lake. He was looking for Littlejohn’s tree frogs, because they are endangered. He recorded audio for five minutes every hour from dusk until the wee hours. He identified numerous species: ground frogs and tree frogs, but, so far, no Litoria littlejohni.

Eastern long-necked turtles

Deb’s particular passion is the eastern long-necked turtle. She invited Ricky Spencer from the Million Turtles Project to come and hopefully introduce turtles back into the lake. She says he looked about and told her they’d be underground and would come out when the season was right. Deb whips out her mobile and shows me a photo that looks a bit like that blurry Loch Ness monster shot. But the long neck is unmistakable. “I was so excited! It was the first eastern longneck we’d seen post fire. Just last week.”

The first sighting of an eastern long-necked turtle post fire (Deborah Wells)

Water management from drought to flood

The lake during the pre-fire drought (Blackheath Campbell Rhododendron Gardens)

The disappearance of water in the pre-fire drought turned the lake into a large mud puddle. Interestingly, the lake and the swamp below are fed almost entirely by Wentworth Street runoff. During the drought, the water was sinking down and going underneath the lake. Deb tells me that to solve the problem, John (who is the head of the Projects Sub-committee and a civil engineer by trade) spent a year researching the rain fall and water flow. “He basically became a hydrologist,” she says.

The 2019 fire was immediately followed by floods.

Flooding rains followed the fires (Blackheath Campbell Rhododendron Gardens)

“We had The Bush Doctor come in and dig pits further up and put in geofabrics and sandstone rock lining to slow the water down. John was able to direct the flow using burns to steer it and when the rain came, it filled up the lake.” Standing next to the lake we pause for a moment. There’s a white heron poised in complete stillness and tadpoles wriggling in the shallow water. “It’s so serene,” I say. Deb nods.

The lake refilled (Blackheath Campbell Rhododendron Gardens)

The Gardens have a wonderful way of including people

Over the course of our conversation, I have become aware of the Gardens’ cultural layering. It’s a beautiful place, magical because people and their lives are threaded through it. This is not just volunteers, but all the people who spend their time there.

Gnomes in the garden (Blackheath Campbell Rhododendron Gardens)

Recently the Gnome Convention drew families into the Gardens: “There were even gnomes in rowboats!” Deb smiled at the memory.

Other events include weddings and people with picnics who enjoy the grassy areas. Deb fondly recalls a goth wedding in the conifer garden where everyone dressed in black robes: “It’s a place to be enjoyed by all people.”

Blackheath Public School come to the gardens as part of their Blackheath history walk each year. This culminates in an Easter egg hunt amongst the rhododendrons. There is a competition to design advertising posters for the Welcome Weeks. One poster is chosen from each year and the winners receive gift vouchers from GleeBooks. All the posters are put up at the Ivanhoe Hotel and families flock to see their children’s work.

Some people just come to the gardens to walk the tracks on the northwest side. You can access these from Ridgewell Road. People are free to walk in the gardens whenever they want. Dogs are permitted even though their smell impacts the habitat for some native species. Deb says it’s a balance between native wildlife and people and dogs being able to enjoy the space. “People are pretty good at picking up dog poo too. We just want to limit the possibility of direct native animal and dog interactions including dogs in the lake that can erode the banks and disturb frog spawn and other lake inhabitants. We also hope that locals who come to the gardens can meet the extremely modest entry fee of $5.”

Deb tells me that most people are pretty good and happy to contribute to caring for the landscape that brings so much joy.

“Some people come to us and ask why they should pay for something that’s their local backyard. We can only tell them that it’s this money that keeps the place running. It pays for toilet paper, fertiliser and other basics. The reason their backyard is so beautiful is because of the tireless efforts of other locals. Obviously, if people come all the time, we don’t expect them to pay every time – two or three times a year makes a real difference. We actually have a card machine in the welcome booth outside the Lodge, so you can make a contribution no matter when or what time you come.”

Deborah Wells

The rewards of volunteering

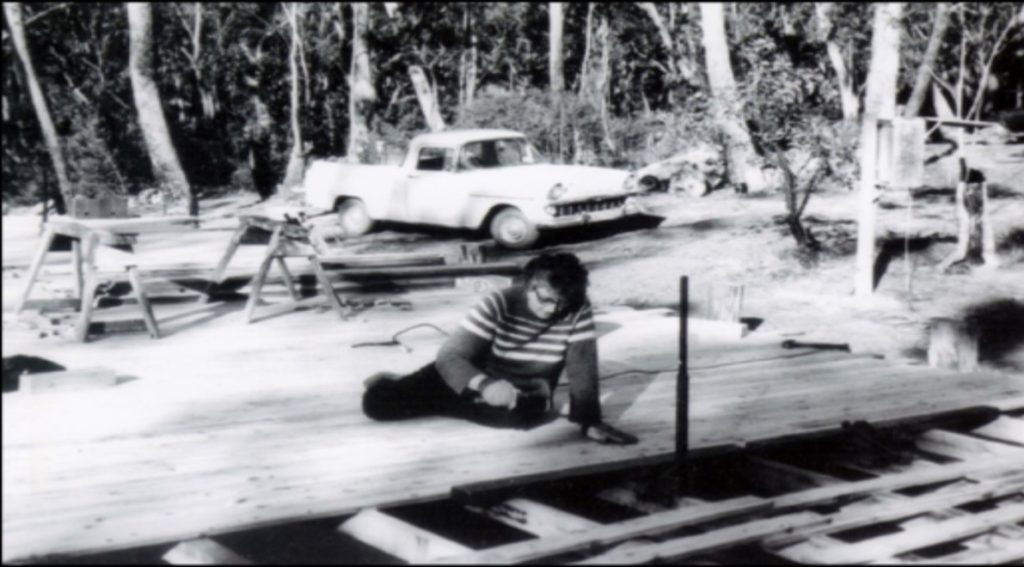

Olive Campbell laying the floorboards for the Lodge (Photographer unknown. Blackheath Campbell Rhododendron Gardens)

On the volunteer front, Deb has showed me a black and white photograph of Olive Campbell laying the original floorboards of the Lodge with hammer and nails in hand. Olive and her husband Noel were instrumental in developing the Gardens, which is why they’re named the Blackheath Campbell Rhododendron Gardens.

“Our volunteers, past and present have such a wide variety of skills,” Deb tells me. “Val, our current treasurer, does an incredible job making sure there is total transparency and efficiency in terms of our finances. She’s not a gardener at all, but makes an extraordinary contribution.”

Jim’s Pond

Jim’s Pond (Hamish Dunlop)

As we walk around the Gardens, Deb points out Jim’s Pond and of course I ask, “Who’s Jim?” Jim was Val’s father, a staunch volunteer. He worked in the garden and when that become too much he would stand at the sink in the Lodge during the Welcome Weeks and wash the cutlery that was too small to go in the dishwasher. Deb says he would stand there for hours and did so until he was 93. Jim left a modest bequest and after the fire had come through Deb saw the possibility of putting in a pond in his honour. “It had to be to do with water,” she says. “Sometimes Val jokes that we should go down to the pond and put some detergent in it.” This makes my heart hurt a little – in a good way. These stories about the way that people and place are bound together, woven together through time and generations, are rich and heartfelt.

Dave is one of the stalwart volunteers who mainly looks after the paths. “If you want to come and work in the Gardens at any stage during the week you can call Dave and he’ll probably say “Come on down.” Every day he drives over an hour each way from Portland to tend ‘his’ garden. He won’t mind me telling you that for him the Gardens are a sanctuary. He has bipolar disorder and caring for the Gardens helps him manage his anxiety – it’s a reciprocal relationship.”

I ask Deb one last question. What do people get out of volunteering and how can people get involved?

“What you get is digging in dirt and being in nature. And the sight and sounds of the wildlife, the birds and so on,” Deb says. “You can gain knowledge. I learnt about cold climate gardening which was one of my reasons for starting.”

Deborah Wells

“You can come to meetings and talks too. Chat to people over afternoon tea. You don’t have to socialise though.”

One lady loves the leaf blower and sweeps the paths and gets a great sense of satisfaction. Another lady specifically looks after that native garden in the middle of the carpark. That’s her garden. No matter what your interest, skill set and skill level, or physical capability, there is always a way you can be involved.” Deb tells me that people from a local supported living house come down with their carers: “They work together with their carer and then come in for morning tea and have a lovely time.”

Sharing values of care and connection to Country

Deb tells me that last year she wanted to find a way to recognise that the Gardens are on Dharug Country, and to pay respects to Indigenous peoples – past, present and future. She got in touch with Chris Tobin, a Dharug man and member of Blue Mountains City Council’s Aboriginal Advisory Council. It was an opportunity to connect all people through the values associated with caring for Country.

Chris created an artwork that will become a feature at the Gardens’ entrance. When I spoke to Chris he told me that the artwork consists of three key symbols: three concentric circles, a gum branch with green leaves and a lyrebird footprint. “I think about the circles being a pebble dropping into water. It reflects an Indigenous concept where the past and future are parts of the present. The ancestors are with us on Country and so are the spirit children of the future. We’re reminded that our responsibility for Country ripples out in all directions and we all have a part we can play.”

Elaborating on the other two motifs, Chris says that the bough with green leaves is a symbol of peace and the third motif is a lyrebird footprint.

“Lyrebirds are protectors of Country. Deb and everyone who looks after the Gardens are taking responsibility for this too. The footprint symbol recognises this and honours our shared values of care and connection to Country.”

Chris Tobin

Deb and I have come back up to the carpark along Centenary Walk. We’re finished up and I thank her profusely for her time and stories. Suddenly Deb spots their resident bower bird. “He has a bower just in behind there. There he is!” she says in hushed tones. It takes me a few seconds to find his body camouflaged by the dense foliage. “We sit here during the Welcome Weeks watching him chase away other birds that come to steal his blue things,” she says. “We put out blue bottle tops over there by the end of the garden and he flies down to collect them.” It’s late in the day and it’s become really still. I take a slow breath and watch the bower bird as he canvasses his territory.

As I drive up the road, I am already thinking about who I am going to introduce to the Gardens next.

Getting Involved

The Gardens are located at Bacchante St Blackheath, New South Wales. Pedestrian Access: Any time, every day of the year. Carpark in Spring & Summer: 9:00am to 6:00pm. Carpark in Autumn & Winter: 9:00am to 4:00pm.

To get involved with the Society you need to become a financial member for $16.50 a year.

There are regular meetings and events, and as a member you will receive the comprehensive newsletter to keep you updated.

Most of the gardening volunteers meet every Monday around 9am. At 10/10:30 morning tea is put on for everyone, and people generally chat about what they’ve been doing in the garden, and socialise more if they like. Lunch is around 12/12:30 – everyone brings their own. After lunch things finish up around 3/3:30.

For more information and contact details visit https://rhodogarden.org.au/. Messages can be left on (02) 4787 8965. They are checked every Monday.

This story has been produced as part of a Bioregional Collaboration for Planetary Health and is supported by the Disaster Risk Reduction Fund (DRRF). The DRRF is jointly funded by the Australian and New South Wales governments.